An introduction to Positive Reinforcement

With infinite ways to communicate and numerous systematic methods we can use to interact with our horses, I choose to use positive reinforcement. As a Windrose Horses client, this is primarily how I’ll teach you to work with the herd. But what is R+?

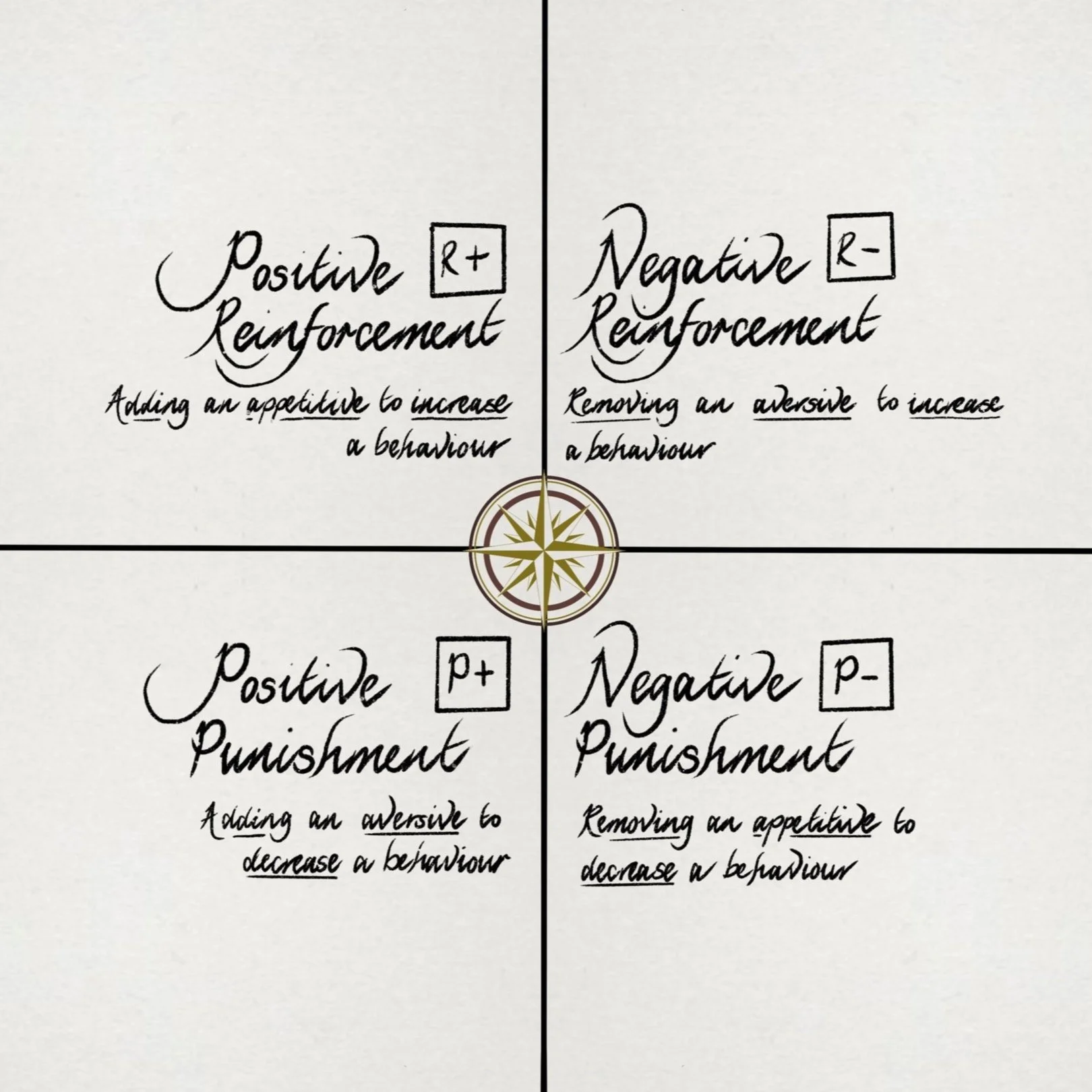

Positive reinforcement is one of four “quadrants” of operant conditioning – a fundamental process through which all organisms learn behaviour. It refers to the learner (in this context, the horse) receiving something they find naturally desirable – or “appetitive” – in order to encourage or increase the expression of a particular behaviour. For example, if I want to teach my horse to stand and wait quietly, I would look to create an environmental scenario that encourages that behaviour and wait for it to occur naturally before immediately rewarding with a few hay pellets or a scratch on their favourite spot. A mechanical clicker is often used to indicate to the learner the exact moment they demonstrated the desired behaviour, enabling precision and clarity. I can then put this behaviour “on cue” – a voice or hand signal for example. Often at the start the learner needs to be clicked and rewarded for a momentary display of the behaviour, and when it is consistently and repeatedly reinforced the duration extends. More complex behaviours need to be broken down into many gradual stages to build it into what is ultimately desired, a process called shaping. Over time I will need to reward less frequently and over longer durations as consecutive behaviours become rewarding in and of themselves and intrinsic motivation builds.

Negative reinforcement (R-) involves applying something the learner finds aversive and removing it as soon as they carry out the desired behaviour. In horse training, this typically looks like the application and release of pressure. In the scenario of teaching a horse to stand and wait quietly, the horse handler may apply pressure on a rope halter until the horse stands still before releasing it; the release reinforces that the preceding behaviour was the one we were asking for.

The “positive” and “negative” in reinforcement does not indicate a judgement of “good” or “bad”. Like a mathematical equation, it simply refers to “adding” or “removing”. Not all pressure is inherently “bad” – indeed neither horses nor we can avoid it in life – and it often elicits great learning. Likewise, rewards can be offered inappropriately and produce dysfunctional behaviour. Ultimately, effective training with either approach requires skill and attunement to the horse. However, with positive reinforcement the motivation and therefore the emotion associated with the behaviour is entirely different to negative reinforcement. R+ trained horses are seeking towards something they enjoy, whilst R- trained horses are seeking relief from something that at best they find mildly aversive and at worst intolerable.

Imagine you have a deadline at work. Your boss is nagging you constantly, until finally you complete the project and the nagging ceases. An aversive has been removed now you have produced the desired behaviour; you’ve just been negatively reinforced. You quite possibly breathe a sigh of relief. Now imagine receiving encouragement and upon fulfilling your deadline your boss says to you, “Great work, let’s go for lunch to celebrate.” You’ve received some praise and have a delicious meal. Your boss even throws a bonus in your paycheque because you worked extra hard. You’ve received an appetitive upon producing the desired behaviour; you’ve been positively reinforced. How does each scenario make you feel? How do you feel about your work? And how do you feel about your boss? All learning has emotion at its core, and when we are interacting with another, the way we teach them affects how they feel about us.

What about the other two ways we learn? Firstly, we have positive punishment. Though this sounds like a contradiction, when we apply that same logic of the mathematical equation, we see that it simply means adding an aversive, this time to decrease or discourage a behaviour. Positive punishment can look like all sorts of things: shouting, hitting, whipping, tying an anxious horse until they stop moving. Finally, there is negative punishment, the removal or withholding of an appetitive to decrease a behaviour. This could be, for example, withholding food or praise, or separating a horse from their bonded partner until their anxious neighing and charging of the fence-line ceases.

Punishment has been shown in numerous studies to not eliminate behavioural issues, but temporarily suppress them. If the horse does not enter a state of shutdown, other dysfunctional behaviours inevitably arise in their place, often to receive further punishment, and the cycle continues. It’s important to note that the most well-meaning of R+ trainers can inadvertently deploy negative punishment by withholding food when the learner is anticipating its receipt. Likewise, negative reinforcement can easily escalate to positive punishment when the horse does not respond as desired to pressure. However, I am adamant that intentional punishment has no place in horse training. In emergencies where safety is at risk we sometimes have to deploy any means at our disposal to de-escalate, and punishment can inevitably creep in. We can however, continually work on our own regulation to remain discerning and proportionate when under duress, and inadvertent punishment should be proceeded with careful, conscious and authentic repair.

The use of positive reinforcement fosters a learning environment where equine effort is recognised and rewarded, even if imperfect, and curiosity is actively encouraged. In us humans, it strengthens patience, non-linear thinking, adaptability, observation skills, responsiveness, clarity of communication and compassion.